As the Prof says, this is entirely do-able, and I’ve done it myself, but it is kind of a hack rather than a fully supported feature.

I work as a Sound Supervisor on TV shows, although I’m more an operator than an engineer. But in very basic terms, in a professional environment, analogue audio works at different levels as follows:

MIC, LINE and AMPLIFIED

A microphone outputs a very low level known as MIC level. This has to go through a pre-amplifier to be boosted to a LINE level. Once at LINE level, all the audio processing hardware can work with it, such as sound mixing desks, outboard audio processors such as compressors or reverb units etc.

The amount of amplification is controlled using a GAIN control. If you’ve ever used an analogue sound mixing desk, although different desks use different ways to skin the same cat - especially at the budget/domestic end of the market, you’ll have seen that they normally have two distinct sockets on the input to each channel, one labelled MIC and one labelled LINE. MIC is usually an XLR socket, while LINE is often a 1/4 inch jack socket. The MIC input routes the audio through the pre-amplifier, while the LINE socket will bypass the pre-amp or do something else to avoid the already high LINE level being amplified further.

Once all the processing is done, the LINE level gets sent to the power amplifier, which boosts it further to a level capable of driving a loudspeaker. Depending on the amp and the speaker, this level is substantially higher than a LINE level, so much so that people talk in terms of watts when describing the level rather than the millivolts used when talking about MIC and LINE levels.

What you need to understand about what you’re trying to achieve is that the level sent to the speaker on a Proffieboard is essentially at loudspeaker level, i.e. the highest level in the chain described above, and what you’re trying to do is drop it back down to a LINE level so you can work with it in other outboard audio stuff. Hence the Prof’s good advice to build some form of protection into your system.

Mono Versus Stereo

Although perhaps a symantic argument, I’ll go into this briefly as I think it’s relevant and does cause lots of confusion. But as the Prof says, Proffieboards work with Mono audio - how could they do any different with only one speaker? But most domestic stuff such as wired headphones uses a stereo mini-jack. Mini-jacks are also sometimes referred to as TRS jacks, the TRS meaning Tip, Ring, Sleeve. The way these are wired is Tip = Left positive, Ring = Right positive, and Sleeve = shared screen (also known as earth or ground). As such, when making an adapter for the Proffieboard, you’ll need to wire the Proffie speaker positive to the tip AND the ring, and the Proffieboard speaker negative to the sleeve. Note however that in strict terms this does NOT give you true stereo - it gives you dual-mono, i.e. two speakers (earphones) reproducing the same sound, as opposed to true stereo in which each speaker reproduces different sound to create a stereo image or soundscape.

Be warned however that there is one more curved ball that catches people out…

Balanced versus Unbalanced

OK, this is where it gets a little more complicated. In professional studio environments, control rooms can be a long way from studio floors, or in the case of music concerts, the stage is at one end of the venue while the sound mixer is miles away at the other end of the venue. If you tried to run unbalanced audio wired like domestic headphones, i.e. a single positive and negative for each source, the cable would pick up all sorts of horrible hums and the audio would be unusuable. Enter stage right balanced audio.

Balanced audio works by using three cores in the wire for each source, wired in such a way that unwanted hums cancel each other out. This is why XLR connectors used for most microphones have three pins rather than just two. This is also why you will see that the first thing a guitar player on a stage has to do is plug the unbalanced output of his guitar into a DI (Direct Injection) box. This converts the unbalanced guitar output to a balanced MIC level output that will then survive the long cable run to the stage control room without inducing unwanted hums along the way.

The reason domestic audio is generally unbalanced is because the cable runs in your living room are short enough that such hums are unlikely to be an issue. Likewise, there’s no need for balanced audio in a lightsaber because it’s so short. And the reason loudspeaker wires only need two cores (positive and negative) is because the level travelling down them is so high that hums just get blown away by sheer horsepower. (It’s more complex that this, but the analogy is helpful).

So why am I bothering to talk about it? I’m talking about it because many audio input devices use the same connectors for their balanced audio inputs that get used for many unbalanced sources. The classic is the 1/4 stereo jack plug. These are widely used for both balanced and unbalanced audio, but the differences in their wiring mean that people are often surprised when they don’t work as intended in certain hardware.

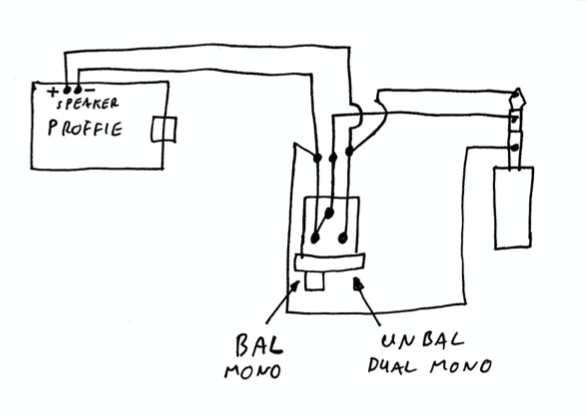

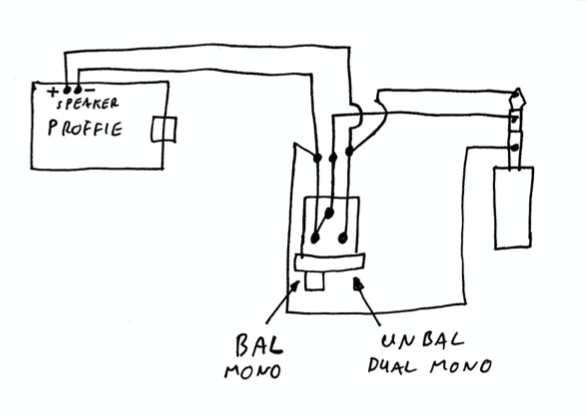

What all this boils down to is that you need to wire your Proffieboard adapter for its specific purpose. So if, for instance, you want to be able to plug your unbalanced stereo headphones into the saber so that only you can hear it, you need to wire it for duel-mono unbalanced as the Prof described. However if you’re planning on connecting your saber to a live PA system that expects a balanced LINE level, you’ll need to wire it differently.

Again, this is somewhat of a hack, but it does work. So for converting your Proffieboard speaker output to a single balanced output from your saber, you’ll need to wire the Proffieboard speaker neg to the jack screen AND the jack ring, then wire the Proffieboard speaker positive to the jack tip. You will then be able to connect your saber to a balanced LINE level input on a sound system or PC soundcard that has balanced analogue inputs. Note that this won’t be TRUE balanced audio, and as such may or may not survive long cable runs. Rather it is a hack that fools the electronics into thinking that they’re getting balanced audio when they’re not. But in domestic situations, it generally works well.

The really good news is that you can make a simple adapter that will do both using a switch. Leaving aside the Prof’s safety measures, the wiring would be as per the sketch below. But as the prof mentioned, with any kind of adapter of this sort, you’ll need to lower the volume of the saber to something the audio system can cope with to get the best results.

Hope that helps.